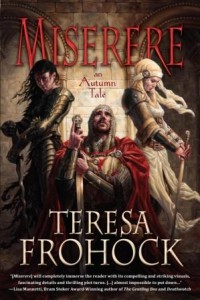

Teresa Frohock on Miserere, Religion, and “Woerld”-Building

Teresa Frohock’s first novel, Miserere, was released in late June, and to celebrate, she’s touring the blogosphere, answering questions about the novel, her process, and her world. Miserere’s concept intrigued me because of the way it combines real religions with a fantastic environment–the garrison universe of Woerld, where chosen warriors from many faiths stand against the encroaching powers of darkness.

I come at religion in my work from a different angle, but as a lover of comparative myth and a child of two divinity school graduates, I couldn’t resist asking:

“How did Woerld, and your fantastical characters and creations, end up anchored in real traditions? When writing, did you ever find yourself torn between the internal logic of your story world and that of the traditions and religions featured in it?”

Here’s Teresa’s answer:

Hey, Max, I’m really glad someone finally asked that.

It really didn’t start that way. It was a long, slow process based on logistics and the butterfly effect, I’m afraid.

Originally, I thought the Katharoi would be like time-traveling wardens to bring escaped demons back to Hell. Then I realized they wouldn’t just be running willy-nilly all over the place, there would have to be some sort of structure to the whole affair. So I created the bastions.

The bastions started out as universities, military academies, but then I realized the different groups would maintain the rites and ceremonies unique to each religion. There was no way to combine them all and have something recognizable.

And I had another reason: I think each religion has something very unique and beautiful to offer its adherents, and to merge them all into one giant religion would lose those distinctive qualities. So I chose to express their commonalities by showing their differences.

Writing Miserere made me realize how little I knew about Christianity. I mean, I knew the basics, but not the history of Christianity, the angelology, the demonology, or Gnostic Christianity and how it all fit together. It was like a whole new world had been opened up to me.

As I researched, I realized there was just a goldmine of legends that never made it into the Bible in addition to recently translated ancient texts on heaven and hell that rendered worlds beyond our imagining. This material was as vibrant as Celtic, Hindu, and Buddhist themes.

As to your second question, I did find myself torn many times. I want to emphasize that Woerld is not a utopian society at all. The Seraphs (or leaders) of the various bastions maintain a constant balancing act between the enduring interests of their doctrines and their need to hold back the Fallen. The bastions can (and will in future novels) experience some of the same frictions they experience in our society. It is inevitable.

No, they’re not all going to get along all the time. I want to keep it real.

However, how the Seraphs and members overcome those differences is what separates Woerld from Earth. Without fundamentalists screaming, they listen to one another. They debate, but they do not argue. There is a great difference between the two, because debate, genuine debate requires that you listen to the other person’s point of view.

The difference between Woerld and Earth is that in Woerld, there are times they must agree to disagree and move on.

Meanwhile, here on Earth, we’re bludgeoning one another to death with doctrine and words.

And so it goes …

Read a summary of and excerpt from Teresa’s novel Miserere, and check out her book trailer, after the jump!